Sarah was the daughter of Thomas Gomme and Mary Eustace, both of Chinnor. Their marriage was recorded in the Chinnor church records in 1773. The Gomme’s had many children, several of whom had died in infancy.

There were as many as 15 recorded births although at least two died in infancy and it seems from the parish records that they used the name again for the next child, which seemed quite common at the time. The two examples of this were Lucy born 1798 and died 1799, followed by another Lucy born in 1800. There was also a James born in 1791 and died in 1792 followed by another James born in 1793 who made it into adulthood as he was still present on the later census returns.

For example, the first Lucy’s birth 24th January 1788, death, June 15th, 1789, making her 17 months old.

By the 1851 census Lucy is described as the householder with all 4 children still at home and an aunt, Charlotte Biggs aged 83 (lacemaker) living with them. James Biggs has died leaving Lucy a widow and she is described in the work status as ‘relieved’ so receiving benefits from the parish. By the next census, in 1861, Lucy, aged 61 is working as a housekeeper for two brothers, Jonah and Edward Britnell on Crowell Hill. Jonah, 67, the head, is described as a proprietor of land and Edward, 48, a wood bailiff. By the 1871 census Lucy was back in the village lodging in the High Street with Harriet Hett, a seamstress born in Maldon, Essex. Harriet’s son William, who was born in Chinnor, also lives there. William is described as a chair turner. There are also two other lodgers. Lucy by this time no longer a housekeeper, but now described as a lace maker. Presumably this was learned in early life from her mother, Mary, who was still lace making in 1841 aged 85, also her older sisters, a useful thing to fall back on when times are hard.

An extract from “The History of Turvey” a village in Bedfordshire

The Truck system was widely used in the area, where the lace maker or a middle dealer is paid in tokens to be used in the shop or even in goods. Perhaps Sarah provided patterns and yarns and traded the finished lace at one of the fortnightly “lace feasts” in the village.

This photo of lace makers in Chinnor was taken from the local book “Chinnor in Camera” which is a fantastic source of village history written whilst many of the memories were still in living memory.

With so many lace makers in one place and so close to the area from which it was reported, it is very likely that this would happen in the Orchard cottages. Perhaps Sarah and her mother facilitated this in Sarah and John’s ‘roomy, comfortable cottage’ as described in the sales advert in 1843. At times it could certainly have been very pleasant sitting outside their cottage making lace in warm weather in the ‘good garden’ and taking in the view of the Chilterns. It would have been very interesting to eavesdrop the possible conversations given the wide range of ages from 8 to 85 years noted on the 1841 and 1851 censuses. Highly likely to be only what they could hear above the clattering of the bobbins which was reported to be extremely noisy. While their fingers flew their tongues would too, sharing local gossip and passing on news and information. The equivalent of The Residents Facebook page. There are interesting snippets of reminiscences of lace makers and their relatives on the ‘Woodlanders Lives’

Some of the finer lace had to be made where there was no chance of soot smuts spoiling it, so coal or wood fires were not permitted.

By 1851 Sarah Guntrip was described as a ‘lace dealer’ and her husband a ‘wood dealer’. The lane was now recorded on the census as “Guntrips” Lane although it seems that it was never formally adopted as such. This suggests that many people needed access to the dealers and would have called it after them as a descriptive term. As it was described as Guntrips Lane in the 1843 advert for the cottages we can assume that either John or Sarah, or both were involved in some sort of trading by then. The recorder for the 1851 census was a William Webster, who appears in the 1847 trade directory as living in Chinnor and noted, interestingly, as a beer retailer, surveyor and schoolmaster. A man of many parts, who would have been aware of the local names for the streets and lanes.

John Guntrip (1778-1853) lived and worked much of his life in and around Chinnor. The Longwick-cum-Ilmer Parish, Buckinghamshire, baptism records tell us that he was born in 1778 to John Guntrip and Elizabeth Fuller who the same records tell us were married in 1765. He had an older sister Elizabeth who was almost 10 years older.

Researching John Guntrip is quite difficult as the most popular first name for male members of the Guntrip family is John according to a chart from ‘Your family history’ based on Census entries.

Great Grandfather Robert did not have such a popular first name. Locally though there were 2 Roberts who seem to have been baptized within a month of each other, unless this is a mistake in the local records as there only seems to be one set of parents. Local records also tell us that there was a Guntrip Field and another Guntrip Lane in the vicinity of Chearsley and Brill at this time.

John Guntrip (1778-1853) was listed on the 1841 census as a Woodsman. Merriam-Webster.com/ dictionary describes the definition of a woodsman as a person who frequents or works in the woods, especially one skilled in woodcraft. First known usage in 1688. Collins helpfully adds that they cut down trees for timber. It will be quite difficult to determine exactly what John did, but it is very likely that originally, he would have worked on the hill cutting wood for chair making, building or firewood. We know that the local bodgers needed timber to shape their chair legs and carve out seats and spars.

Perhaps this is how he began, to supply them with cut timber to shape on their pole lathes or spoke shave on their stools. This would have been very physical work which would have become more difficult as he became older. Coppicing was carried out up on Chinnor Hill to ensure replenished supplies of strong straight timber for construction and regenerate thinner branches for firewood or lighter construction. There is clear evidence of it still amongst the tall straight beeches on the top of Chinnor Hill near the chalk cross.

Coppice Merchants bought standing coppice, then contracted with woodsmen on a piece-work basis to cut and sort the wood. They sold on the produce to supply local craftsmen and then were responsible for disposing of the brash to leave a clean floor and ensuring that the new growth was protected by stock-proof hedges. Countrywide there only were between 150 and 200 coppice dealers who controlled of the industry. Coppice dealers as opposed to firewood dealers were a lot less common, so it is most likely that John was a firewood dealer rather than a coppice dealer.

“See a barge blunder through, overbearing and shabby,

With its captain asleep, and his wife in command;”

Nowadays it is mostly pleasure craft that pass through.

There are similar records of wood being transported from Mapledurham:-

"The accounts of Thomas West of Wallingford, part owner of a barge and one of several owners who took wood fuel to London from the Oxfordshire Chilterns, refer to carrying '10 loads of billet and 20 loades of talle wood' from Mapledurham to Cranes Wharf, London..” from the accounts of Thomas West.

In 1850 a bundle of 100 Faggots for firewood would have cost £1. A faggot was a term used for any type of twiggy wood, it also included roots. The woodsman was paid approximately 1 shilling in the pound for his part in cutting and preparing the wood into bundles, including binding it with withies. As a dealer John would have made more money from this than he would have done as a woodsman. As he got older this may have been a less taxing job. By 1841 he would have been in his sixties.

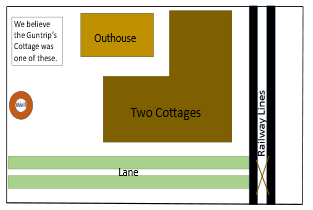

It would seem from the layout of the cottages and the potential size of the out houses it would have been unlikely that he dealt in large size pieces of timber unless he possessed additional storage. Given that the lane became known as Guntrips Lane we can assume that he carried out his business there and whatever he needed to store fitted into the outhouses. It would be interesting to know if the big shed behind house on 1841 map is of any relevance to John’s business. Perhaps some test pits in future SOAG excavations could show up something to help us understand this more.

Although John was described in 1851 census as a wood dealer, we have evidence that he may have been a dealer before this time and possibly before 1843 when the cottages were advertised for sale declaring the Lane to be Guntrip’s Lane.

By the 1861 census it had reverted to Hollans Lane. Both Sarah and John died between 1851 and 1861 so they did not feature on the 1861 census. We are not sure when they took up the rental of the cottage before the census records began but it is fair to say that they were there for around 20 years, possibly longer, especially as we know that Sarah was still there until her death in February 1859, very likely dying in the cottage.

We know there was only one lace dealer and one wood dealer in Chinnor in 1851, (from the census summary in the VCH) and so this must have been our John and Sarah.

Snippets of history help to complete the picture of the life of our Orchard Guntrip family. John Wade recorded as living with his wife Esther in the cottages in 1841 had been born in Chinnor in 1770. In September 1833 marriage Banns were published in St Andrews Church registers between John, who was then living in Lewknor, to a Hester Foley of Chinnor. In the same month banns were also issued in the church at Lewknor. The actual marriage took place on the 25th of September 1833 at St Andrews, Chinnor, being the parish in which Hester lived. John and Hester had both previously been married John being described as a widower and Esther as a widow. On the certificate John signed his name but Esther has merely placed her “mark” indicating that she was not able to sign her own name as was fairly common at this time. It is interesting to note that as one of the usual two witnesses was John Guntrip (who unable to write, made his mark) and who was recorded in 1841 as their neighbour in Hollands Lane when the census began. Could he have been a witness because he was already a neighbour of one or both of them perhaps in Lewknor (something for further research)?

It is interesting that in the census the lane had reverted to, and was recorded as, Holland Lane in the poll records of 1885, some 24 years after the 1861 census, certain Chinnor inhabitants, namely James Rogers, James Rogers Junior & Joseph Rogers, indicated that they lived in “Guntrips Lane” - so although the name was, and had been for some time, formally known as Holland Lane some inhabitants seem still to have remembered, and still referred to it as “Guntrip’s Lane”. Despite the death of the Guntrips, their name lived on!

In an amendment to the Tithe award Act in 1859 the names of the main householders are listed as: Lucy Biggs, John Folley*, Sarah Guntrip, William Marriott*, Jacob Bishop*, Mary Anne Munday, those marked with an asterisk are shown 3 years later in the 1861 Census. Sarah Guntrip died in February of 1859, soon after the amendment. Lucy Biggs mentioned here, at this time aged 59, was Sarah’s sister according to records, although she could possibly have been her daughter given dates. Lucy was nearly 18 years younger than Sarah.

This pair were quite enterprising and obviously well known locally in their day but also still remembered many years later when the Rogers family still kept their memory alive by stating their home as being in Guntrips Lane on the allotment register as late as 1902 despite the census reverting to Hollands Lane. Mabel Howlett in an interview in 2005 was still referring to it as Guntrip’s Lane from her living memory. She had lived in the lane until the 1970’s. It is also interesting to note that the current name for the Lane, Donkey Lane is most likely attributable to The Rogers family, one of whom was very likely to have been known as Donkey Jimmy. Who kept Donkeys in the lane and shod them in one of the outhouses of the remaining properties sometime before and around WW1.

This is a story that will continue to grow as we learn new facts about the people who lived here and their lives. Thank you for reading this and following our journey of discovery.

Carol Stewart July 2013.

Works and memories cited:

“Firewood from the Oxfordshire Chilterns” by Pat Preece.

SOAG – Bulletin no. 58. 2003

Woodland Trust- https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/plant-trees/managing-trees-and-woods/

Hambleden Lock - Wikipaedia

Chilterns AONB – Coppicing. https://www.chilternsaonb.org/coppicing

Local Research – Bernard Braun

Aston Rowant and Spring line villages. – https://www.astonrowant.wordpress.com

Woodlanders Lives -https://www.chilternsaonb.org/.../woodlanders-lives-and-landscapes

Thames poems- https://www.thames.me.uk/thamespoems

Chinnor in Camera

British History Online (british-history.ac.uk)

Victoria Online History

The Autobiography of Joseph Bell of Olney, written 1926

No comments:

Post a Comment